Notes on "Clean Code in Python" — Design by Contracts (DbC)

This post talks about a design practice called Design by Contract (DbC) in Python context, with an example from JAX codebase. I came across this concept in "Clean Code in Python: Develop maintainable and efficient code, 2nd Edition". I find this practice ubiquitous in various open source Python codebases, so I would like to document its principle and try to apply it in the future.

What is Design by Contract (DbC) and Why Need it?

We write a programme for a specific purpose. The programme could be either a function or a class method. So long as we feed the “right” inputs to it, ideally it should do exactly what we intend. No more and no less. Like pop method is meant to remove the last element from its list instance in-place, and sorted function is meant to make a copy of a list instance with its elements sorted.

But we are prone to mistakes, so is a programme. In practice, it is not surprising for a programme to do or output something out of our expectation. It could go wrong for various reasons, such as erroreous logics, negligence of corner cases, or incompliant users feeding wrong inputs to the programme. The root cause could easily become intractable when the programme are nested with complex logics. For the reason above, it is naive for us to safely assume a programme does what we intend. We should have a mechanism to safeguard this. When it goes out of its intension, the mechanism should be able to surface it promptly, so as to signal the developers for a fix and isolate the error from the subsequent programmes. Design by Contract (DbC) is invented for this purpose.

DbC is a software design practice to enforce responsibilities on both parties, programme and user, to ensure a programme to do what we intend. As the name suggests, the practice works like a contract. It entails the responsibilities that both parties have to observe. So long as the responsibilities are satisfied, it garantee the programme behaves correctly. If the programme goes wrong, it could quickly surface the issue and easily trace which party breaks its responsibilities.

Key Pillars of Design by Contract

Just like a contract is typically composed of several sessions, DbC typically contains several components: Precondition, Postcondition, Invariants and Side Effects. It is a good practice to document them to inform the users about the essential “terms and conditions” of the programme.

Among these components, Precondition and Postcondition are the core because they are the responsibilities applied on both parties. As an analogy, they serve like two separate inspectors in a manufacturinng factory. One responsible for gating the quality of the raw materials, another responsible for checking the quality of the end product. The factory could functions perfectly thanks to the diligence of these two inspectors.

🕍 Precondition

Simply put, Precondition is the inspector gating the inputs that the user feed to the programme. The programme can’t behave as intended without the “right” inputs. If the inspector finds that the inputs do not observe to the contract, it invalidate the inputs and raise out to the user. In this instance, the responsibility belongs to the user because one fails follow the “terms and conditions” of the contract.

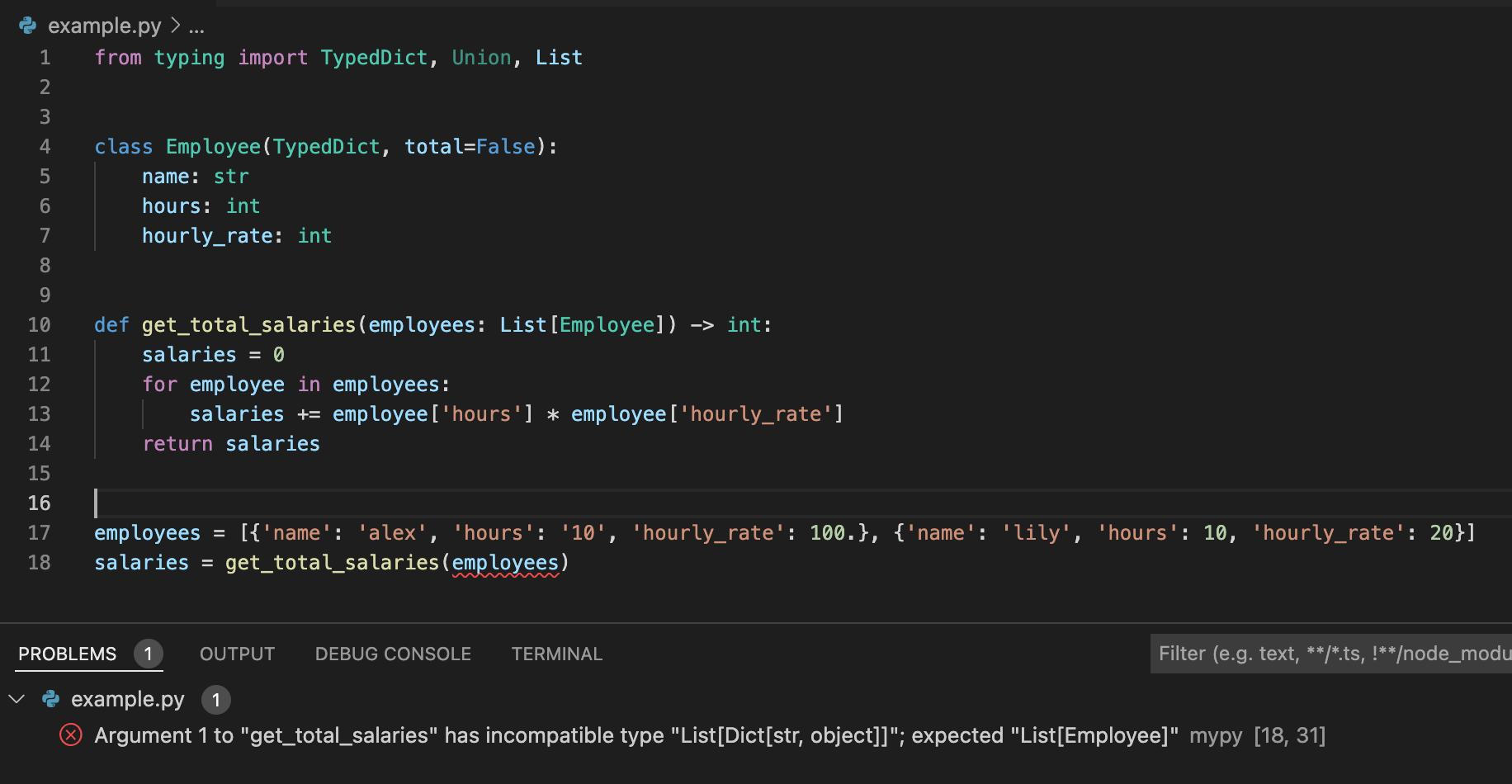

Typical things to validate on the inputs are their types and properties. For example, you could validate the input is an instance of np.ndarray with dimension of 2. It is a good habit to document these validation rules in your doc-string. For types, we could instead handily annotate them in function signature, thanks to the introduction of type annotation since Python 3.6.

Such annotation gives clear instructions to the users about the types of inputs and outputs. In addition, it is convenient to debugging because we could check the type compliance with static analysis tool such as MyPy in your IDE. This approach compacts the type information into your code, sparing additional effort to document them in doc-string. Having said that, type annotations in Python only serves as a soft compliance, meaning that failure of type compliance doesn’t raise any error.

🛕 Postcondition

Contrary to Preconditon, Postcondition is the inspector gating the outputs that the programme return. If any miscompliance is found in the outputs, it would raise out to the user. It helps isolate the issue quickly and prevent the “wrong” outputs further propagate to subsequent programmes.

Similar to precondition, typical things to validate on the outputs are their types and properties. For example, you could validate the output has a np.ndarray type without any np.nan values. As mentioned above, we could annotate the expected types of the outputs by function signature.

🌠 Invariant

Invariant is another component probably highlighted in the contract. I find this term popping up a lot in programming, but I did’t quite understand what it means at the beginning. It actually means something pretty conceptual. It refers to a property that always holds true in a programme. It’s a property that you can safely assume in order for the programme to function well. For example, sorted always returns a new list whose entries are sorted.

🚨 Side Effects

Optionally, you can also highlight the side effects in the contract.

Side effects is any operations in a programme that change the state of things out of its local scope. It may sound confusing when you first come across the meaning of side effects. To make a few examples, changing the value of a global variable is a side effect because the function intends to change the state of a variable that doesn’t live in the function. Other examples of side effects are mutating the values of an input that you feed to the programme, or raising an error to terminate the entire process.

It is worthwhile to highlight the side effects, if any, because these are things that Precondition and Postcondition fail to capture.

Examples from JAX Codebase

It’s worth taking a look at an example to consolidate the idea. As my personal preference, I take a function from JAX codebase as an example because I am recently picking up the framework - broadcast_shapes

broadcast_shapes receives any number of shape instances as inputs. A shape represents the dimensions of any tensors. It is expressed as a tuple of int. Given the shapes as inputs, broadcast_shapes attempts to find out the ultimate shape after broadcasting is applied on each axis of the inputs.

For example:

from jax.numpy import broadcast_shapes

broadcast_shapes((1, 1, 5), (3, 1, 1), (1, 4, 1))

# (3, 4, 5)

🔎 A Brief Look at the Source Code

broadcast_shapes internally triggers another function of same name but living in a private module jax._src.lax.lax. We extract the code snippet associated to broadcast_shapes below:

# code snippet extracted from jax._src.lax.lax

def broadcast_shapes(*shapes: Tuple[Union[int, core.Tracer], ...]

) -> Tuple[Union[int, core.Tracer], ...]:

"""Returns the shape that results from NumPy broadcasting of `shapes`."""

# NOTE: We have both cached and uncached versions to handle Tracers in shapes.

try:

return _broadcast_shapes_cached(*shapes)

except:

return _broadcast_shapes_uncached(*shapes)

@cache()

def _broadcast_shapes_cached(*shapes: Tuple[int, ...]) -> Tuple[int, ...]:

return _broadcast_shapes_uncached(*shapes)

def _broadcast_shapes_uncached(*shapes):

_validate_shapes(shapes)

fst, *rst = shapes

if not rst: return fst

# First check if we need only rank promotion (and not singleton-broadcasting).

try: return _reduce(_broadcast_ranks, rst, fst)

except ValueError: pass

# Next try singleton-broadcasting, padding out ranks using singletons.

ndim = _max(len(shape) for shape in shapes)

shape_list = [(1,) * (ndim - len(shape)) + shape for shape in shapes]

result_shape = _try_broadcast_shapes(shape_list)

if result_shape is None:

raise ValueError("Incompatible shapes for broadcasting: {}"

.format(tuple(shape_list)))

return result_shape

def _validate_shapes(shapes: Sequence[Shape]):

def _check_static_shape(shape: Shape):

checked = canonicalize_shape(shape)

if not all(idx >= 0 for idx in checked):

msg = f"Only non-negative indices are allowed when broadcasting" \

f" static shapes, but got shape {shape!r}."

raise TypeError(msg)

If we try to apply DbC framework to analyse broadcast_shapes, we will notice it has both Precondition and Postconditions. Let’s find them out one by one!

📍 Identifying Precondition

Notice most of the heavy lifting jobs are done in _broadcast_shapes_uncached. From there we see that _validate_shapes is the helper function that validate the inputs so it is in fact serving as Precondition.

def _validate_shapes(shapes: Sequence[Shape]):

def _check_static_shape(shape: Shape):

checked = canonicalize_shape(shape)

if not all(idx >= 0 for idx in checked):

msg = f"Only non-negative indices are allowed when broadcasting" \

f" static shapes, but got shape {shape!r}."

raise TypeError(msg)

What _validate_shapes does is to standardize (they call it canonicalize) the types of each shape instance and verify that they all only contain positive int. Otherwise, the programme raises a TypeError. If we find this error upon using broadcast_shapes, it means we are complying to the rules set in the contract.

Additionally, we can see from broadcast_shapes’s signature that each shape is expected to have a type of Tuple[int, ...].

shape is actually Tuple[Union[int, core.Tracer], ...]. core.Tracer is a special type designed by JAX specifically used for abstract evaluation rules. This type is only internally used in JAX and its function is out of the scope of this blogpost. You could safely ignore it for now.

📌 Identifying Postcondition

From broadcast_shapes’s signature, we can see that a new shape instance is expected to return and it should have a type of Tuple[int, ...].

_try_broadcast_shapes attempts to find a valid shape as a return but it doesn’t garantee to find one because the shapes provided may not be compatible to the broadcasting rules. Therefore, the programme has to check if a valid shape has been found at the end. The way it does is to check if result_shape is None. The programme raises ValueError if no valid shape is found.

if result_shape is None:

raise ValueError("Incompatible shapes for broadcasting: {}"

.format(tuple(shape_list)))

However, there is one caveat here. When it comes to which party is responsible, the context here is slightly different. Failure of Postcondition doesn’t imply a critical flaw in broadcast_shapes. Instead it means by nature broadcasting can’t be done on the provided shapes. broadcast_shapes implicitly assumes its users understand the broadcasting rules.